|

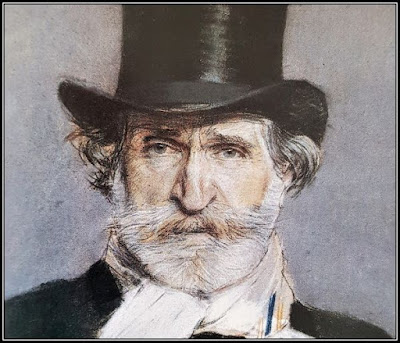

| Giuseppe Verdi, the composer who transformed Italian opera and became a symbol of national identity. |

Giuseppe Fortunino Francesco Verdi was born in 1813 in Le Roncole, a tiny village in the northern Italian province of Parma, near Busseto. His parents ran the village’s only shop. They were poor and uneducated and never learned to read or write. Yet their son’s musical talent must have appeared early: they bought him a spinet, a small keyboard instrument, and by the age of twelve Verdi was already serving as organist in the village church.

|

| The house in Le Roncole where Giuseppe Verdi was born in 1813. |

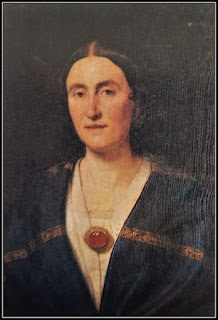

At the age of eighteen, Verdi applied to the Milan Conservatory but was rejected—officially for exceeding the age limit, though his unorthodox technique also played a role. Once again, Barezzi intervened, financing private studies in Milan. After returning to Busseto, Verdi—still not yet twenty-three—married Barezzi’s daughter, Margherita.

Success and tragedy

|

| Margherita Barezzi, Verdi’s first wife, whose early death deeply marked the composer’s life. |

Salvation arrived unexpectedly. The director of La Scala urged Verdi to set a libretto based on the biblical captivity of the Jews under Nebuchadnezzar. The result was Nabucco, premiered in 1842, which transformed Verdi overnight into Italy’s most celebrated composer.

Late MasteryAround 1860, Verdi ceased writing operas on commission. From this point on, he composed only when deeply compelled to do so. Don Carlos emerged from his fascination with Schiller and the challenge of French grand opera. Then followed a long silence: between 1873 and 1885, Verdi composed no operas at all.

“Life in the Sweatshop”

Fame spread rapidly across Europe. Verdi himself described the following years as “my life in the sweatshop”—composing relentlessly to meet theatrical demand. Between 1842 and 1851, he wrote fourteen operas. While not all were masterpieces, they secured his financial independence and public stature.

A decisive artistic turning point came in the early 1850s with the creation of three operas that redefined Italian opera: Rigoletto (1851), Il trovatore (1853), and La traviata (1853). At the same time, Verdi became deeply associated with the Italian Risorgimento. His name itself became a patriotic slogan: “Viva VERDI”—secretly standing for Vittorio Emanuele Re d’Italia. The Austrian authorities failed to recognize that the nation was celebrating not only its composer, but also its future king.

During these years, Verdi’s personal life stabilized. He formed a lasting partnership with the soprano Giuseppina Strepponi, whom he married in 1859.

|

| Giuseppina Strepponi, soprano and lifelong companion of Verdi; the couple married in 1859. |

Astonishingly, at the age of seventy-two, he returned with Otello, a monumental setting of Shakespeare, created in collaboration with Arrigo Boito. Even more surprising was what followed: at eighty, Verdi completed Falstaff, a comic opera of extraordinary wit, lightness, and lyrical brilliance—his final masterpiece.

Giuseppina Strepponi died in 1897. Verdi spent his final years in Milan, where he died in January 1901. He had requested a simple funeral, without music. Yet as his coffin passed, an immense crowd gathered spontaneously and began singing—first softly, then with overwhelming force—the famous Chorus of the Hebrew Slaves from Nabucco.

Comments

Post a Comment